Wyman Departs from San Francisco

San Francisco to Oakland

[This is Chapter 3. The story begins here…]

May 16, 1903 — San Francisco, California

"Little more than three miles constituted the first day's travel of my journey across the American continent. It is just three miles from the corner of Market and Kearney streets, San Francisco, to the boat that steams to Vallejo, California, and, leaving the corner formed by those streets at 2:30 o'clock on the bright afternoon of May 16, less than two hours later I had passed through the Golden Gate and was in Vallejo and aboard the "Ark," or houseboat of my friends, Mr. and Mrs. Brerton, which was anchored there. I slept aboard the "Ark" that night. At 7:20 o'clock the next morning I said goodbye to my hospitable hosts and to the Pacific, and turned my face toward the ocean that laps the further shore of America. I at once began to go up in the world. I knew I would go higher; also I knew my mount. I was traveling familiar ground. During the previous summer I had made the journey on a California motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada, and knew that crossing the Sierras, even when helped by a motor, was not exactly a path of roses. But it was that tour, nevertheless, that fired me with desire to attempt this longer journey - to become the first motorcyclist to ride from ocean to ocean.”

George A. Wyman

July 11, 2016 — San Francisco, California

It's a typical summer day in downtown San Francisco — the sun is strong but not hot as cars, buses, street cars, and pedestrians battle for every inch of forward motion. The din of the city bounces off the asphalt and the facades of the tall office buildings that block out the sun.

I ride the Zero motorcycle through the gridlock, filtering to the front of red lights and eavesdropping on phone conversations and car stereos as I pass. The Zero is electric and, unlike gas-engined motorcycles that rumble and roar, is completely silent at red lights. I cross Market Street, then ride up a curb cutout and park illegally beside Lotta's Fountain. It was easier than I thought it would be; everyone is too busy staring at their phones to mind, and after I park, they just filter around the bike and wait for the Walk sign to give them permission to leave this little triangle of brick made by three intersecting streets.

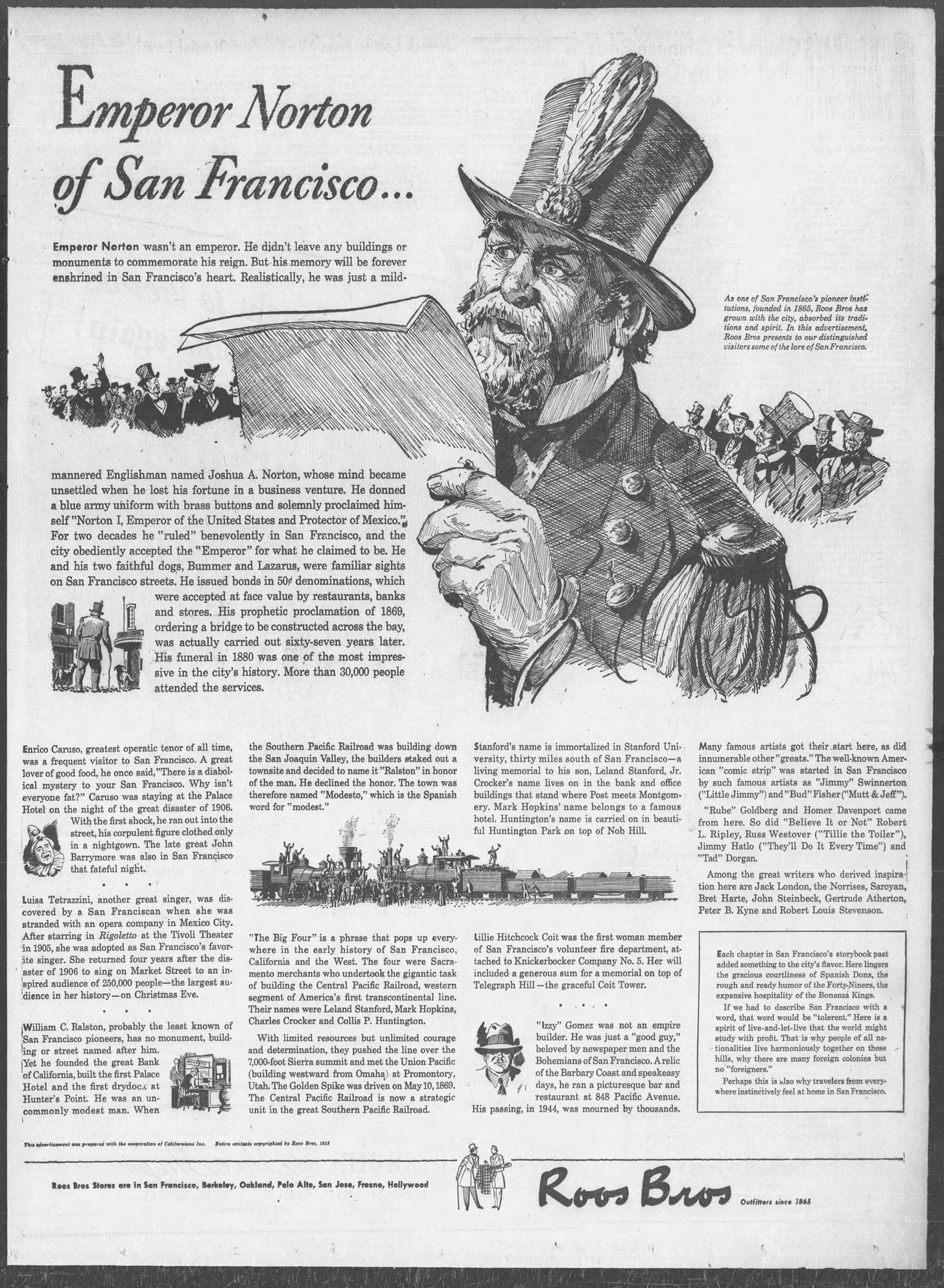

Lotta’s Fountain, an ornate bronze-painted, cast-iron relic from the Gilded Age is nearly as invisible as the motorcycle and I, attracting nary a glance. But it has seen things since being donated by actress Lotta Crabtree in 1875, from soldiers returning from war to home teams celebrating championships and parading down Market Street. And in 1903, Lotta's Fountain watched a young man named George A Wyman straddle a newfangled motor-bicycle and ride east on Market Street. His destination? New York City and a place in history as the first person to cross the country with a motor vehicle.

I stand there nearly as immobile as Lotta's Fountain, absentmindedly watching people and cars scurry by while lost in thought. I'm on the precipice of the biggest trip of my motorcycle life—The Great American Cross Country Road Trip—and I'm excited and nervous and nervous and excited. And anxious too. Did I mention that I was nervous? I've dreamed about riding from coast to coast for decades, literally, yet The Great American Cross Country Road Trip had somehow eluded me. To be honest, I'm that one that's been doing the eluding, with a lifetime of now's-not-the-right-time and blah blah blah excuses. But now, I'm finally here, thanks to George.

George A Wyman crossed my desktop just a couple of months earlier and the story of his derring-do (I'm assuming they said things like "derring-do" in 1903) was both inspiring and a reminder of my own inability to make my own Great American Road Trip happen. It was just the kick in the butt that I needed. One thing led to another…furtive emails pitches to RoadRUNNER Magazine (a magazine where I’d been a longtime contributor) checking my calendar and work schedule to see what was feasible, and a little bit of “eff it all, if you don’t do this now you may never do it.” Introspection…and here I stand, ready to start my own cross country adventure…with the wrong motorcycle. Don't get me wrong, the 2016 Zero DSR that I am riding is a fine example of the rare breed of motorcycles that use electricity instead of gasoline for propulsion. But compared to a gasoline-powered bike, it can't get very far, just 88 miles at 55 MPH. Read that again - 88 miles at 55 MILES PER HOUR. I can't remember the last time I rode a motorcycle at 55 MILES PER HOUR.

I blame Florian at RoadRUNNER. I pitched the story idea of following Wyman's route across America, telling them, "If there was one story that RoadRUNNER should be the lead publication on, it's this one." They agreed. With their contacts in the motorcycle industry, they could have secured any number of high speed, high comfort, cupholder-compatible, continent-crushing, gas-powered motorcycles for this trip. With the right bike and enough caffeine, I could do this trip in 50 hours. In fact, the Wyman Memorial Project, an organization dedicated to spreading Wyman's story, hosts an annual ride that does just that. But Florian's perfectly sound reasoning was that I should attempt this trip with something as groundbreaking and revolutionary as Wyman's gas motorcycle was in 1903. Easy for him to say—he wouldn't be the one riding—but he was right. Electric motorcycles are still as rare as hen's teeth today, less well known than Teslas and other electric cars and crossing the country with one will not be a walk in the park.

In fact, just two people have managed to cross the country with an electric motorcycle. In June 2013, "Electric" Terry Hershner became the first individual to ride an electric motorcycle (a Zero also) from sea to shining sea, narrowly beating the Moto-Electra team with their electrified Norton and generator-equipped chase vehicle. Then, just two months later, Ben Rich, on another Zero electric motorcycle, arrived at Google headquarters with the Ride the Future team (which included a Nissan Leaf, an electric scooter, and an electric bicycle) to become the second. Should I make it to New York City in one piece, I'll be the third.

The 88-mile range of the Zero DSR is just one half of the problem. The other half is recharging time. When plugged into a standard household 120 volt outlet, the Zero DSR can take up to eight hours to charge. That's OK for overnight charging but waiting that long in the middle of the day would basically kill that day's forward progress. Luckily, the Zero DSR has an optional ChargeTank that will let me charge at many car charging stations (not Tesla, though) in as little as a couple of hours. Still, I have to make it across Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Iowa, where compatible charging stations are rarer than self-control at an all-you-can-eat buffet; some are 500 miles apart. I've got a trick or two in the topcase though; I sure hope they work. Worse yet, I might run out of charge on a lonely road in the middle of the hot desert, where the gas cans of good Samaritans would be useless and nothing less than a tow vehicle could save me. And just in case I'm on a road so lonely that there aren't even good Samaritans, I've packed Plan B…a pair of running shoes.

All of this crosses my mind as I stand there with the Zero, both of us still invisible. "Jump and the world will catch you," my cousin Christine once told me. And now that I'm here at Lotta's Fountain, there's nothing left to do but jump. I take a couple photos, get back on the Zero, and turn the key. The dashboard flashes and it's on, utterly silent but on. I check for pedestrians and cars, twist the throttle, and the nearly silent motorcycle whirs forward on a wave of electric torque.

San Francisco is more than double the size than when Wyman was here, and the streets are filled with cars, trucks and buses trying to flatten me like a pancake. Thankfully, the Zero is a scalpel in a drawer full of butter knives and I slice my way through midday San Francisco traffic and hop on the Bay Bridge. There was no bridge across the Bay in 1903 but in the 1870s a homeless man (the self-proclaimed "Norton I, Emperor of the United States") would roam the streets in an army uniform with gold epaulets and a beaver hat and make crazy proclamations, like calling for a bridge to connect San Francisco with Oakland. It took until 1936 for the good emperor's vision to be realized and today, I'm on that bridge. There's a new section that looks like the future, with gleaming towers of white holding up impossibly thin cables.

My trip today is shorter than Wyman's as I stop in Oakland to visit Tom and Nancy. Tom’s been a friend since the Radio Shack TRS-80 computer was a thing. We geeked out on computers when we were kids then he drove out to California in the late 80s in a '72 Plymouth Duster and never came back. In the 90s we rode bicycles from Oakland to LA along the PCH and had the time of our lives. These days, we sometimes go years without seeing each other, but whenever he's back East or I'm out West we try to hang out. Nancy is Tom's wife and the best decision that Tom ever made. When they got married, beneath a canopy of giant redwood trees, they rode unicycles.

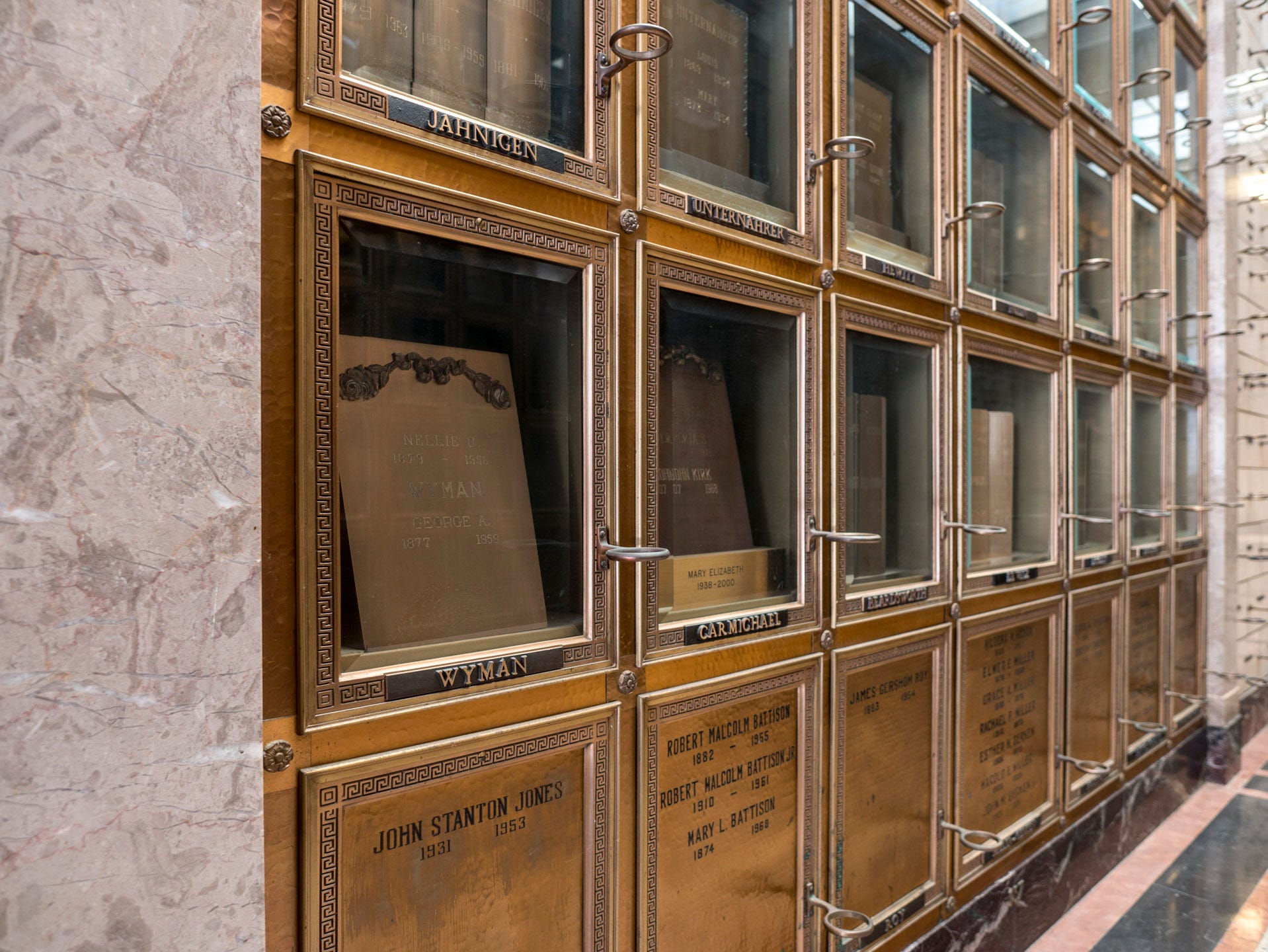

After running an extension cord from the basement to the bike, we hop on bicycles and ride to a local gastro pub where Tom gets free beer for life (He occasionally works for beer). We eat and drink and catch up on life. The next morning, Tom and I head to Mountain View Cemetery to look for Wyman and his wife Nellie in the mausoleum. After twenty minutes of trying to make sense of the byzantine numbering system in the mausoleum, we find them on one of the upper floors. I stare at the bronze plaque bearing the names George A. Wyman and Nellie G. Wyman, speechless. Here lies a true pioneer and his wife. Here lies a man who is all but unknown to the thousands of motorcyclists that have unwittingly followed his trail. Here lies the man whose tire tracks I will follow across the wide-open spaces of the continent.

Mr. Wyman, I am embarking on a trip to follow your tire tracks to New York City. Along the way, I will look for evidence of your passing. Truth told, I'm a little anxious about the distance and logistics of the trip and cannot even begin to imagine the challenges that you faced in 1903. Respect, sir. I hope to see you in New York.

Please share this Substack with your adventurous family and friends…

Sofa so good John! (That's from my years in the furniture industry.)