Up and Over the Sierra Nevada

From Sacramento, California to Reno, Nevada on an electric motorcycle

Apologies for the lengthy time between updates. Projects of this scope are daunting, and I've never been good at that attention span thing. But this Wyman story is my white whale. Eight years after I took my trip, and over 120 years since Wyman took his, Wyman's name is still unknown among motorcyclists. He deserves more recognition for his pioneering ride. So I'll continue to hack away at the pile of words sitting on my hard drive and try to do my part to set that right. Thanks for your patience. And thanks to the friend for the gentle nudge to continue this project. You know who you are.

…john

[This is Chapter 5. The story begins here. I recommend viewing on a laptop or desktop or even a tablet to let the photos breathe a little more.]

May 18, 1903 — Sacramento, California

"It was late when I awoke, and almost noon when I left the beautiful capital of the Golden State. The Sierras and a desolate country were ahead, and I made preparations accordingly. Sacramento's but 15 feet above sea level; the summit of the range is 7,015 feet. Three and a half miles east of Sacramento the high trestle bridge spanning the main stream of the American River has to be crossed, and from this bridge is obtained a magnificent view of the snow-capped Sierras, "the great barrier that separates the fertile valleys and glorious climate of California from the bleak and barren sagebrush plains, rugged mountains, and forbidding wastes of sand and alkali that, from the summit of the Sierras, stretch away to the eastward for over a thousand miles." The view from the American River bridge is imposing, encompassing the whole foothill country, which "rolls in broken, irregular billows of forest crowned hill and charming vale, upward and onward to the east; gradually growing more rugged, rocky, and immense, the hills changing to mountains, the vales to canyons until they terminate in bald, hoary peaks whose white, rugged pinnacles seem to penetrate the sky, and stand out in ghostly, shadowy outline against the azure depths of space beyond."

George A Wyman

July 13, 2016 — Sacramento, California

I unplug the Zero from it's night with a soda machine and explore local roads running alongside the railroad in an industrial part of Sacramento that few outside of those that work or do business there ever see. The area has sprawled beyond all recognition since Wyman’s time, so much so that the only things Wyman would likely recognize today would be the railroad tracks and the hazy, jagged horizon line marking the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Nearly everything else — the paved roads, the cars, the traffic lights, the drive through coffee shops, etc… — would blow his mind like a modern day Rip Van Winkle.

"A few miles from Sacramento is the land of sheep. The country for miles around is a country of splendid sheep ranches, and the woolly animals and the sombrero-ed ranchmen are everywhere. Speeding around a bend in the road I came almost precipitately upon an immense drove which was being driven to Nevada. While the herders swore, the sheep scurried in every direction, fairly piling on top of each other in their eagerness to get out of my path. The timid, bleating creatures even wedged solidly in places. As they were headed in the same direction I was going, it took some time to worry through the drove."

George A Wyman

Sheep were displaced years ago by housing developments and shopping centers. But with each passing mile suburbia yields to rural countryside. I follow old US 40 as it connects quiet, small towns set between fields of tall, brown grass and small stands of trees. This was one of the original US highways but it was designated over 20 years after Wyman’s trip. Even this stretch, part of the original Lincoln Highway, did not exist when Wyman rode through here.

"The pastoral aspect of the sheep country gradually gave way to a more rugged landscape, huge boulders dotting the earth and suggesting the approach to the Sierras. At Rocklin the lower foothills are encountered: the stone beneath the surface of the ground makes a firm roadbed and affords stretches of excellent goings. Beyond the foothills the country is rough and steep and stony and redolent of the days of '49. It was here and hereabouts that the gold finds were made and where the rush and "gold fever" were fiercest. Desolation now rules, and only heaps of gravel, water ditches, and abandoned shafts remain to give color to the marvelous narratives of the "oldest inhabitants" that remain. The steep grades also remain, and the little motor was compelled to work for its "mixture". It "chugged" like a panting being up the mountains, and from Auburn to Colfax- 60 miles from Sacramento-where I halted for the night, the help of the pedals was necessary."

George A Wyman

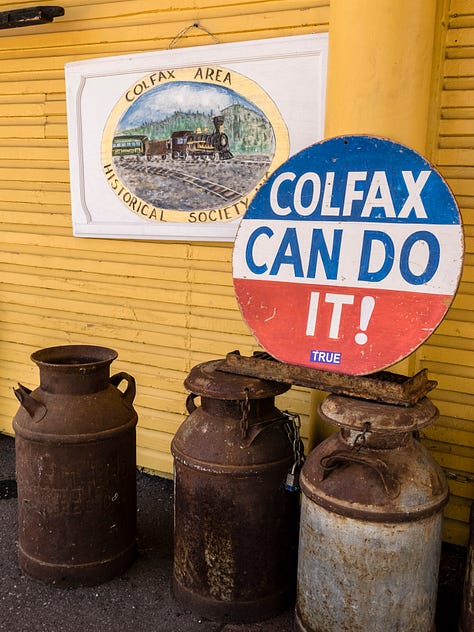

The land tips upward and the road serpentines through the thickening forest while the railroad tracks zig and zag their way up the incline. By the time I get to Colfax, I’ve climbed over 2,300 feet and there is more to come. But first I need a charge and a bite to eat. I locate an electric car charging station near the railroad tracks and a building that looks old enough to have seen Wyman pass through.

While plugging in, a man walks by, confused at seeing a motorcycle at a car charging station. He's got the California "dude" standard issue uniform - baggy shorts, flip flops, a loose t-shirt, a baseball cap, and a quick smile. "Junior" has never seen an electric motorcycle before and is surprised to hear that the Zero is made in California. I answer the questions that I will get dozens of times on this trip:

Junior: "How far can it go?"

Me: "88 miles at 55mph."

Junior: "How long does it take to charge?"

Me: "2-3 hours at a charging station like this."

And then Junior throws a changeup.

Junior: "What do you think about what's happening in this country right now?"

Apparently, Junior's been camping with friends and just heard about the shooting of police officers in Dallas. I tell Junior, "The shooting was terrible but the news wants you to think that the country has gone crazy so that you'll watch more news. Once you get out into the real world you see that nearly everyone is just trying to get by." I must have passed the test because Junior nods in agreement and when I ask for a local restaurant recommendation, he says, "I'll walk you to one." We cross the tracks and head to Main Street, a two-block collection of old Western style buildings, many with false fronts and sidewalk awnings.

Once again, I wonder if these buildings saw Wyman. Junior walks into Cafe Luna — a quirky little Mexican restaurant with interesting art on the walls — like he owns the joint, and asks the waiter if the owner is around. She's not, so Junior asks him to take care of me while he goes and looks at some crystals in a nearby shop. As I order lunch the waiter confesses to never having met Junior before, and I imagine that's the last I'll see of him. But it's not. A half hour later, Junior returns to make sure that everything is ok. It is — the food is quite good, actually — and I offer to buy him something to eat. He declines, wishes me luck on my journey, and leaves.

After lunch, I stop by town hall. The town is very much vested in Wyman's story; the mayor rides a motorcycle. One of the town employees walks with me to the exact same spot where Wyman stood to have his photo taken. The old train depot in the photo is gone though; today it is a parking lot. I stand on the hot asphalt and think about his trip.

I head back to the bike to check on the state of charge. I’ve got some more time to kill, so I meander over to the Colfax Area Heritage Museum housed at the train station. The place is filled with mementos from an earlier time. I ask about Wyman’s era and visit a large conference room where large, oversized railway maps hang from the walls. I stand on a chair to take some photos of the maps, get right up close to the lines and dots that mark the stops and section houses of Transcontinental Railroad, and imagine Wyman studying similar maps.

Back outside, I visit the Wyman plaque that the town has recently installed by the railroad tracks. And then, with the bike charged, I hit the road.

"When I left Colfax on the morning of May 19, the motor working grandly, and though the going was up, up, up it carried me along without any effort for nearly 10 miles. Then it overheated, and I had to "nurse" it with oil every three or four miles. It recovered itself during luncheon at Emigrants' Gap, and I prepared for the snow that had been in sight for hours and that the atmosphere told me was not now far ahead. But between the Gap and the snow there was six miles of the vilest road that mortal ever dignified by the term."

George A Wyman

My afternoon is spent riding on smooth roads rising through steep hillsides dense with evergreens as the midday sun filters through the trees. It’s quiet and peaceful, as if the forest floor of pine needles is muffling the world, and the hum of the Zero motor is barely noticeable as it propels me through the conifers. Every once in a while I catch a glimpse of the more earnest I-80, semis rumbling uphill, cars revving past.

"Then I struck the snow, and as promptly I hurried for the shelter of the snow sheds, without which there would be no travel across continent by the northern route. The snow lies 10, 15, and 20-feet deep on the mountain sides, and ever and anon the deep boom or muffled thud of tremendous slides of "the beautiful" as it pitches into the dark deep canyons or falls with terrific force upon the sheds conveys the grimmest suggestions."

George A Wyman

There is no snow on the roads in July of 2016 but the altitude can certainly be felt. Trees give way to an enormous rock garden with boulders the size of modest vacation homes. I crest another hill and Donner Pass suddenly unfolds before me, rocky peaks stretching to the far horizon while a slender ribbon of asphalt snakes down towards a deep blue lake. A blanket of green clings to the lower elevations and the sky is a crystal blue. In the thin air, it’s taking my breath away. I pull off to the edge of the road and just stare.

I cannot help but think of the early Native Americans and pioneers getting to this vantage point without the benefit of roads or motors. I imagine Wyman here too, and the countless others who have stood here with their mouth agape at the sheer beauty of it all. I start descending but I’ve gone less than a half mile before I pull off again, still gobsmacked, to snap more photos and descend some more. And then I look up towards the peaks and see the snow sheds high above me.

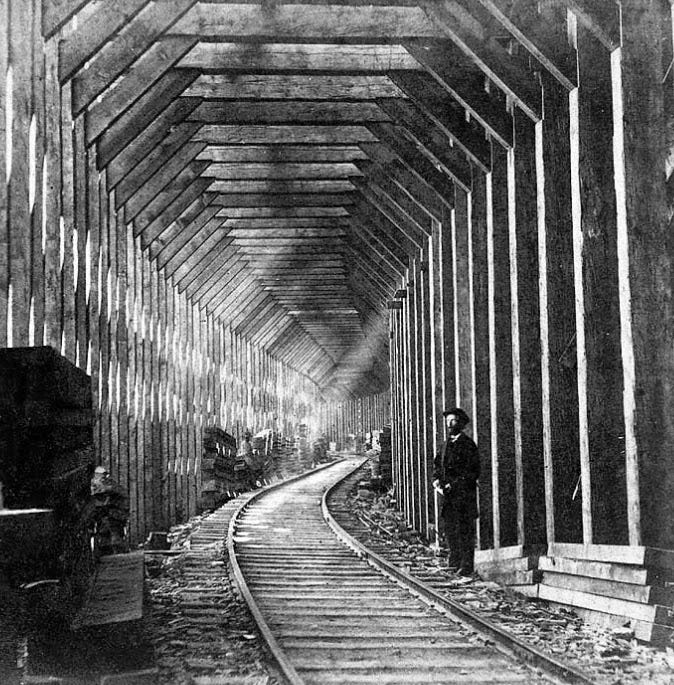

"The sheds wind around the mountain sides, their roofs built aslant that the avalanches of snow and rock hurled from above may glide harmlessly into the chasm below. Stations, section houses, and all else pertaining to the railways are, of course, built in the dripping and gloomy, but friendly, shelter of these sheds, where daylight penetrates only at the short breaks where the railway tracks span a deep gulch or ravine.

To ride a motor bicycle through the sheds is impossible. I walked, of course, dragging my machine over the ties for 18 miles by cyclometer measurement. I was 7 hours in the sheds. It was 15 feet under the snow. That night I slept at Summit, 7,015 feet above the sea, having ridden - or walked - 54 miles during the day."

George A Wyman

After the monumental completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, the Union Pacific Railroad was faced with the problem of snow on Donner Pass. The pass could get up to 70 feet of snow in the winter, which could literally stop a train in its tracks. Their answer was to build forty miles of snow sheds over the pass, wooden structures that kept the snow off the tracks. The Donner Historical Society describes the snow sheds as, "… dark and gloomy and the smoke from the locomotive was just as trapped as the passengers, filling the sheds and the passenger compartments. What could have been one of the best train trips in the world was very unpleasant." Eventually, the flammable wooden snow sheds were replaced by concrete and today some of them lie unused as the Union Pacific Railroad re-engineers sections of the pass. But in Wyman's time they were wooden, still in use, and still miserable.

"The next day, May 20, promised more pleasure, or, rather, I fancied that it did so, l knew that I could go no higher and with dark, damp, dismal snow sheds and the miles of wearying walking behind me, and a long downgrade before me, my fancy had painted a pleasant picture of, if not smooth, then easy sailing. When I sought my motor bicycle in the morning the picture received its first blur. My can of lubricating oil was missing. The magnificent view that the tip top the mountains afforded lost its charms. I had eyes not even for Donner Lake, the "gem of the Sierras," nestling like a great, lost diamond in its setting of fleecy snow and tall, gaunt pines.

Oil such as I required was not to be had on the snowbound summit nor in the untamed country ahead, and oil I must have - or walk, and walk far. I knew that my supply was in its place just after emerging from the snow sheds the night before, and I reckoned therefore that the now prized can had dropped off in the snow, and I was determined to hunt for it. I trudged back a mile and a half. Not an inch of ground or snow escaped search; and when at last a dark object met my gaze I fairly bounded toward it. It was my oil! I think I now know at least a thrill of the joy experienced by the traveler on the desert who discovers an unsuspected pool."

George A Wyman

Photos of Wyman and his California motorcycle show a very sparse and utilitarian setup, a far cry from the sophisticated kit a modern cross country motorcyclist carries. A modern touring motorcycle like a Honda Gold Wing or BMW R 18 Transcontinental can weigh north of 800 pounds and features conveniences lik remote locking luggage as well as radar-regulated cruise control, six speed transmissions, and electronically adjustable windscreens. The drivetrains themselves are modern engineering marvels, capable of traveling thousands of miles without any maintenance whatsoever. For most modern riders, the days of carrying extra lubricating oil have been left far behind.

"The oil, however was not of immediate aid. It did not help me get through the dark, damp, dismal tunnel, 1,700 feet long, that afforded the only means of egress from Summit. I walked through that, of course, and emerging, continued to walk, or rather, I tried to walk. Where the road should have been was a wide expanse of snow - deep snow. As there was nothing else to do, I plunged into it and floundered, waded, walked, slipped, and slid to the head of Donner Lake. It took me an hour to cover the short distance. At the Lake the road cleared and to Truckee, 10 miles down the canyon, was in excellent condition for this season of the year. The grade drops 2,400 feet in the 10 miles, and but for the intelligent Truckee citizens I would have bidden good-bye to the Golden State long before I finally did so."

George A Wyman

Donner Pass, a place that once struck fear into the hearts of travelers and took years for the Central Pacific Railroad to conquer, is now a vacation spot, with a ski resort at the top and pleasure boats plying Donner Lake. Winter snowfall is still extreme, averaging over 400 inches per season, but road crews are quick to clear the roads. And in July, my trip over Donner Pass is significantly easier than Wyman's, particularly since the Zero does not require any oil to run.

I descend the pass on perfectly smooth pavement and within the hour I am eating dinner at a nice restaurant in Truckee while the Zero DSR charges.

"The best and shortest road to Reno? The intelligent citizens, several of them agreed on the route, and I followed their directions. The result: Nearly two hours later and after riding 21 miles, I reached Bovo- six miles by rail from Truckee. After that experience I asked no further information, but sought the crossties, and although they shook me up not a little, I made fair time to Verdi- 14 miles. Verdi is the first town in Nevada and about 40 miles from the summit of the Sierras. Looking backward the snow-covered peaks are plainly visible, but one is not many miles across the State line before he realizes that California and Nevada, though they adjoin, are as unlike as regards soil, topography, climate, and all else as two countries between which an ocean rolls.

Nevada is truly the "Sage Brush State." The scrubby plant marks its approach, and in front, behind, to the right, to the left, on the plains, the hills, everywhere, there is sage brush. It is almost the only evidence of vegetation, and as I left the crossties and traveled the main road, the dull green of the plant had grown monotonous long before I reached Reno, once the throbbing pivot of the gold-seeking hordes attracted by the wealth of the Comstock lodes, located in the mountains in the distance. That most of Reno's glory has departed did not affect my rest that night."

George A Wyman

After dinner, I am admiring a pair of fully-loaded touring bicycles parked on the corner when their owners arrive. A brother and sister duo from Arizona, they are cycling from Arizona to the Pacific Northwest. Tonight, their aunt, also a motorcyclist, treated them to dinner. It is encouraging to see that the next generation still has the spirit of adventure

I make a beeline to Reno in the fading light. I've got enough charge to wind the Zero out and stretch it legs and it obliges, rocketing me along Interstate 80 at extralegal velocities. The heat of the day is long forgotten, replaced by a growing chill that seeps through my summer riding gear. I tuck behind the windscreen, twist the throttle a bit little more, descend from the Sierra Nevada, and watch the lights of Reno grow in my visor.