(New readers, the story begins here…)

George Adams Wyman was born in 1877 in Oakland, California, to George Wellington Wyman (originally from Waltham, MA) and Georgeana Stickney Wyman (originally from Illinois). George had one younger brother, Frank A. Wyman, three years his junior.

Not much is known about young George's life, but the September 4, 1896 issue of the San Francisco Call newspaper has one of the earliest mentions of Wyman’s name as an entrant in the one mile and half mile handicap bicycle races at Goodwater Grove in Stockton, CA. Bicycle races were “handicapped” back then, with slower racers allowed to start with an advantage that the stronger racers would seek to overcome. For this race, Wyman was handicapped 95 yards, one of the biggest handicaps of the heat. In other words, Wyman, judged to be one of the weaker riders in the field (and quite possibly a new racer) was given nearly a football field head start. The day after the race, the San Francisco Call described Wyman’s heat, "The final was a beautiful race. The riders lay closely bunched to the last eighth, when Mott drew clear and without effort wrested first position from Wyman, A.C. (95 yards), who got the place from Webb, I.C.C. (90 yards), in 2:18 2-5."

Wyman raced regularly for several years for Oakland's Acme Wheelmen. He was talented but not exceedingly so, often finishing midfield despite handicaps. He did have a surprise victory in San Jose in May 1897 but only because all of the riders in front of him crashed. Wyman was quoted as saying, "I was back in about tenth position and just rode through the wreck, bumping into a fallen man here and riding over a broken wheel there, but without being thrown from my wheel. I rode on and won the race, nobody being left to contest with me."

By 1901, Wyman was racing for Oakland's Reliance Athletic Club, and by 1902 he was a member of San Francisco's Bay City Wheelmen. Besides that dubious victory, Wyman's racing career was otherwise unspectacular.

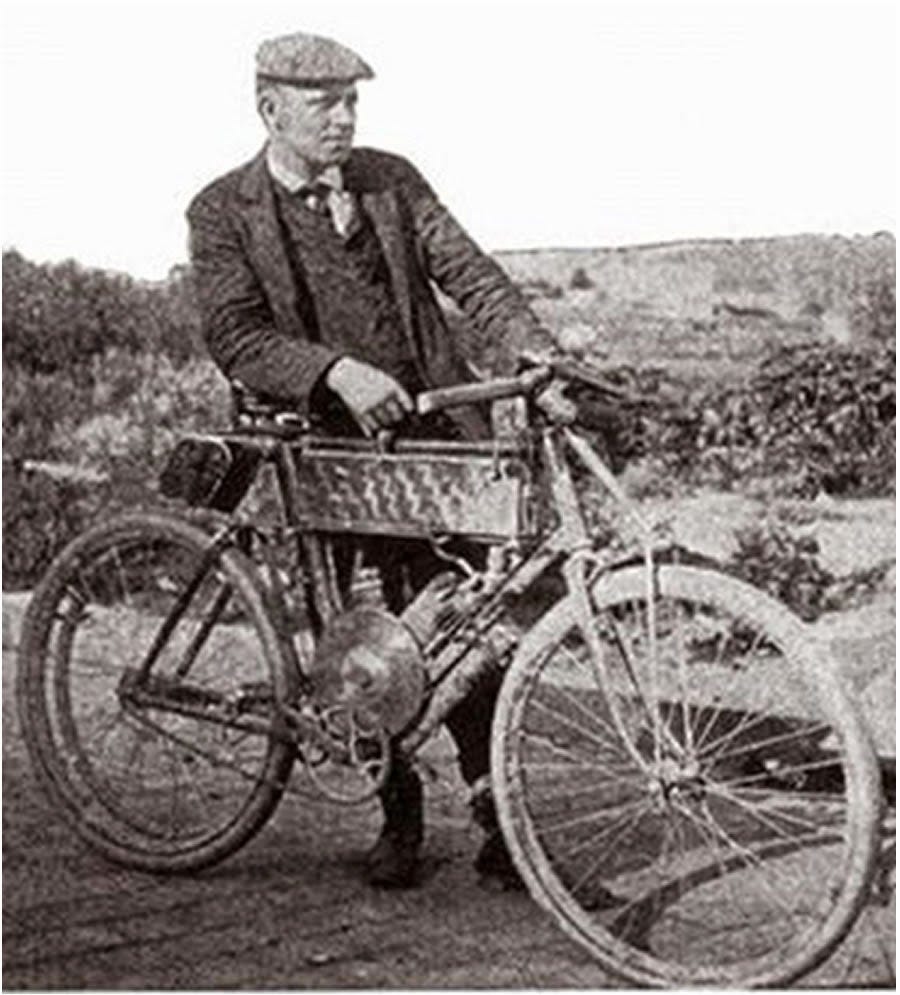

After five plus years of bicycle racing, Wyman caught onto another trend. In 1902, he bought a “motor bicycle.” We know them today as motorcycles, but in 1902 they were so new that people had not settled upon what to call them[2]. Wyman's California motor bicycle retained many aspects of the safety bicycle—the double diamond steel frame, the equal-sized front and rear spoked wheels with pneumatic tires, the seat and handlebars, and the pedals, crank and chain. But it also had a motor grafted onto it. The motor was small by modern standards, just 200cc, featured an exposed flywheel, sat just above the pedals, and connected to the rear wheel via a leather belt and pulley system. The left side of the rear wheel (opposite the bicycle chain) featured a large hoop nearly the diameter of the wheel itself that received the leather belt from the motor and drove the wheel and motor bicycle forward.

Above the motor and hanging below the horizontal top tube was a metal box containing fuel and oil supplies, a (primitive for today but advanced for its time) "carburetter" that mixed "gasolene" and air for the motor, and an electrical coil for providing spark. As with all other motorcycles of the time, the California ran on stove fuel, available at general stores. Running on this 30 octane "gasolene" (modern automotive gasolines are 85 octane and higher), the California produced 1.25 horsepower, or about as much power as a small push lawnmower today. California claimed that the motor bicycle could go as far as 200 miles on a single gallon of gasolene. Stopping for this 90-pound motorcycle was provided via a coaster brake on the rear wheel and a duck brake (a pad pressed down upon the top of the rubber tire when a handlebar lever was squeezed) for the front wheel.

This was truly the Jurassic age of motorcycles. Indian Motorcycles had been founded a year earlier in Springfield Massachusetts. Also in 1902, a bicycle manufacturer in England produced its first motorcycle. The name of the company? Triumph. And 21-year-old William S. Harley and brothers Arthur and Walter Davidson were building their first motor bicycle in a machine shop in Milwaukee. They would not finish until 1903.

Wyman's fascination with bicycles and motor bicycles was not uncommon; the entire country was mesmerized by new modes of personal transportation. Yes, the railroad had conquered the continent, and large cities had begun laying rails and operating trolley cars to deal with a massive influx of people from the countryside. But many local trips were still taken with horses. New York City alone had 100,000 horses in 1900 (versus 4,192 cars sold in the entire country that year) providing all manner of transportation services like carriage rides and the horse buses. But an undesirable byproduct of all of these horses was 1,200 metric tons of poop and 100,000 liters of pee every day. Converted to English units, that's a shitload of crap (literally) that littered the streets, attracted flies, and must have smelled like a bed of roses on a hot summer's day. It was a problem that vexed major cities around the world; in 1894, the Times of London estimated that by 1944 the entire city of London would be buried under nine feet of manure.

It was within the context of this olfactory assault that the bicycle, the motorcycle, and the car seemed like such a breath of fresh air. And they were cheaper to own and operate too. In 1895 a new publication was introduced, The Horseless Age[3], and they enumerated the advantages of the motor vehicle over the horse,

"From the gradual displacement of the horse in business and in pleasure, will come economy of time and practical money-saving. In cities and in towns the noise and clatter of the streets will be reduced, a priceless boon to the tired nerves of this overwrought generation. Then there is a humanitarian aspect of the case. To spare the obedient beast, that since the dawn of history has been man's drudge, from further service at the industrial treadmill, will be a downright mercy. On sanitary grounds too the banishing of horses from our city streets bill be a blessing. Streets will be cleaner, jams and blockades less likely to occur, and accidents less frequent, for the horse is not so manageable as a mechanical vehicle."

The Horseless Age, Vol. 1, No. 1, page 2.

It is no surprise then that Wyman appeared to be quite enamored with his new toy. So, in September of 1902, when his Bay City Wheelmen were scheduled to go to Reno, NV for a race against the Reno Wheelmen, Wyman asked his teammates to take his racing bicycle with them on the train while he rode his new toy to Reno. To our modern sensibilities, this is no big deal; you can hop on Interstate 80 and get to Reno in about three hours while listening to podcasts, sipping lattes, and all but ignore the daunting Sierra Nevada mountain range lying between the two cities. But in Wyman's era it was. The daunting 7,056 ft Donner Pass is part of the original California Trail and was made infamous by the Donner Party of 1846 who were stranded there by deep snow and resorted to cannibalism to survive. It was also one of the chief engineering challenges of the Transcontinental Railroad and took the Central Pacific Railroad nearly five years, four tunnels, miles of snowsheds, and two "Chinese Walls" to surmount. And when Wyman arrived in Reno, he became the first person to ride a motorcycle over the Sierra Nevada. It was a big enough deal to warrant a mention in the local newspaper.

"First Motor Cycle to Cross the Mountains

George A. Wyman, a member of the relay team of the Bay City Wheelmen, arrived in Reno Sunday. He has the distinction of being the first person to ride a motor cycle over the Sierras. The machine he traveled on was a California motor touring wheel of 1 1-4 horsepower.

The only pedaling he did was on some of the heaviest grades. He had no mishaps on the trip.

Mr. Wyman will remain in Reno and will ride with the Bay City's if the big race is pulled off next Sunday."

Daily Nevada State Journal, Tuesday, September 2, 1902

Besides the lucky bicycle race victory, this was likely George A. Wyman's first significant achievement. His Bay City Wheelmen lost to the Reno Wheelmen but Wyman's ride across the Sierra Nevada gave him an idea.

The following April, The Bicycling World and Motocycle (sic) Review reported that Wyman was contemplating crossing the country on his motorcycle.

“Wyman may Cross Continent

George A. Wyman, of San Francisco, is the first motor bicyclist to disclose across-the-continent symptoms. If he is able to perfect the necessary arrangements, as is likely, he will undertake the long trip early this summer.”

The Bicycling World and Motocycle (sic) Review, April 25, 1903

Less than a month later, on May 16, 1903, Wyman shoved off from Lotta’s Fountain in San Francisco and entered the flow of streetcars, horse drawn carriages, pedestrians, and automobiles. Wyman’s motorcycle had an extra rack at the back to carry tools, parts, and other travel items, but that’s it. He had no logistics or support crew, no official sendoff from elected officials, prominent citizens, or media, no fanfare. He did have a folding pocket Kodak camera that he was going to use to document his trip for The Motorcycle Magazine, a new publication that was going to launch with stories of his trip.

On the day that Wyman left, the headlines of the San Francisco Call recounted President Roosevelt’s visit to California and trip to Yosemite National Park, and antisemitic rioting in Kishinev, Russia that resulted in 49 Jews killed, hundreds of houses destroyed, and shops pillaged. The sports page reported that recently traded pitcher Cy Young beat his former Sacramento squad, 9-8. There was one automobile for sale in the classifieds, steam powered and in “fine condition; for sale cheap”. And there were nine ads for horses and wagons for sale.

Just two days after Wyman departed Lotta’s Fountain, Horatio Nelson Jackson, a physician visiting from Burlington, Vermont, was sitting in the University Club of San Francisco at 722 Sutter Street, a short walk from the fountain. Perhaps flush with the energy of the city or from the driving lessons that he and his wife had been taking, Jackson made a $50 wager with other club members that he could drive an automobile across the country, from San Francisco to New York. It was a pretty brash bet considering the fact that nobody had managed to do it yet. Not only that, but Jackson had neither an automobile or a license to drive one. But by May 23rd, Jackson not only managed to learn how to drive, he also secured the services of another driver, Sewall K. Crocker, a chauffeur (and another bicycle racer) from Oregon, purchased a nearly new 1903 Winton automobile, and loaded it with supplies for the voyage. While Wyman and Jackson weren't officially racing against each other, they were racing for a place in history.

Lots of research here, John. Fascinating.

Wow, so interesting!