[The story begins here… I recommend viewing on a laptop or desktop or even a tablet to let the photos breathe a little more and help convey the vastness of the American West.]

Clouds stretched thin by an invisible breeze streak the sky. The sky is so big here that it dwarfs the mountains. You might not notice it as much in a tin-topped car but when you are on a motorcycle beneath a sky like this you’d have to be blind (which is a bad way to be riding a motorcycle) not to feel its expanse. As the day progresses the heat rises and so does the haze. I join I-80 and put in some miles.

Wyman was not inclined to appreciate the stark beauty of Nevada though, he was too busy just trying to cross it. After the previous day’s challenge of the Forty Mile Desert, he was once again faced with more desert and more sand on the way to Winnemucca.

"This is where I made a sad mistake A 10-mule team could not haul a buggy through the sand there, and after going 3 miles and getting half a mile away from the railroad tracks, I got stuck in the sand hopelessly. I found that the trail did not lead to Winnemucca anyhow. It took me an hour to push the bicycle by hand back again to the tracks across the sand hills. When I wanted to rest, though, the sand was useful, for the bicycle stood alone, and once I took a snapshot of it while it was thus set in the sand. This is the place where the automobiles that try to cross the continent come to grief."

George A Wyman

Wyman may have been referring to the 1901 cross country attempt by Alexander Winton and Charles Shanks. Winton, founder of the Winton Motor Carriage Company in Cleveland, OH, had been making cars since 1897. They sold over 100 cars in 1899, making them the largest automotive manufacturer in the country, bigger even than a rival company owned by a fellow named Henry Ford.

From the beginning, Winton saw the PR potential of taking his automobiles on long trips to prove their durability. In 1897, Winton and his shop superintendent Wm. A Hatcher left Cleveland on July 28 in a two-cylinder Winton automobile that ran on cleaning fluid. Along the way, they purchased fuel at hardware stores. 800 miles and eleven days later the pair arrived in New York City. There wasn’t much fanfare when they arrived, but back home in Cleveland Winton’s trip drew additional investors and customers.

In May 1899, Winton repeated the Cleveland to New York trip, this time with Charles Shanks, a reporter from the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Shanks sent daily reports of this 707 mile trip to dozens of newspapers (his repeated use of the French word "automobile" helped to establish the word in the national lexicon) and stimulated even more interest in Winton Motor Carriages.

Then, in 1901, Winton and Shanks (who by now was working for Winton in public relations), attempted the biggest trip of them all, across the country from San Francisco to New York City. Nobody had managed it yet; in fact, they were the second ones to even attempt it.

After leaving San Francisco, Winton and Shanks struggled over the Sierra Nevada, relying repeatedly on their block and tackle to extract them from mud and snow and raging streams. They made it, though, and were the first to successfully drive over Donner Pass, a year before Wyman even. With the mountains behind them, they thought that the rest of the trip would be much easier in comparison. They were very wrong. Thirty miles west of Winnemucca, they were advised to load the car onto a railroad flatcar because the next thirty miles were particularly difficult. They did not heed the advice and paid for it. The pair were repeatedly stuck in the Nevada’s sand. Shanks wrote, "progress was slow. The sand became deeper and deeper as we progressed. At last the carriage stopped, the driving wheels sped on and cut deep into the bottomless sand." Winton and Shanks got as far as Mill City before finally giving up. Defeated, they left the automobile axle deep in the sand, hiked to Mill City, and caught the next train to Cleveland, sending a crew with horses to retrieve the car. Winton was so thoroughly defeated by the sands of Nevada that he advised others to avoid the state entirely.

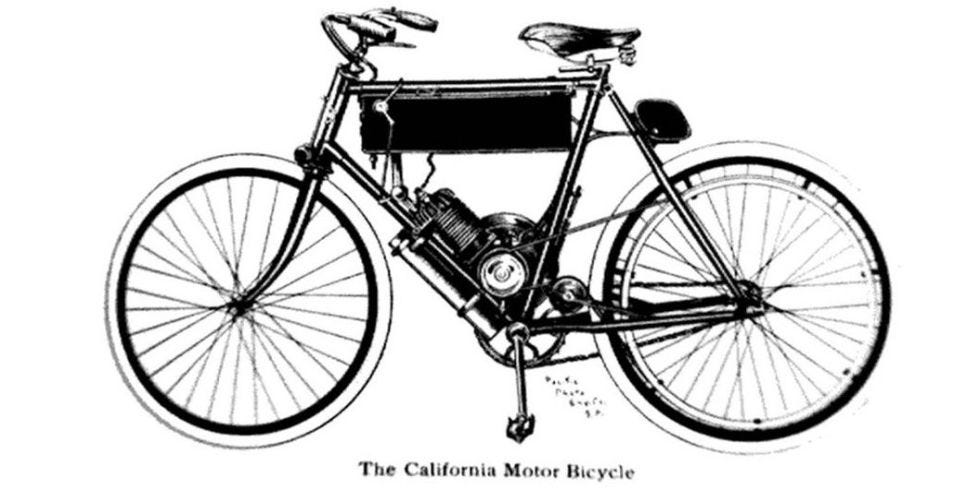

Wyman pressed on where Winton and Shanks had given up. Thankfully, Wyman’s California motorcycle did not weigh the 400, 500, and 600+ pounds of modern motorcycles. It was closer to 100 pounds, which is light but not a trifling, and he was pushing it through deep sand. But that wasn’t his only problem.

"In the struggle with the bicycle, I lost my revolver and my wrench through a hole in my pocket, and I lost an hour looking for them, but I found them in the sand. I wouldn't have lost that revolver for a great deal. It furnished me with all the fun I had in my loneliness. I did not have any occasion to draw it in self- defense, but I practiced my marksmanship with it on coyotes- they pronounce it ki-o-tee out here, with the accent on the first syllable. It is a long .38 that I carry, and a remarkably good shooter. I could hit a coyote with it at 200 yards, and left several carcasses of them in the desert."

George A Wyman

Today, I-80 floats over the sands without breaking a sweat and deposits me into Winnemucca. Wyman called this place a "cattle town" where he got some gasoline and "put a plug of food in my stomach, which had been without breakfast." But to my modern eyes it’s a veritable metropolis compared to Lovelock, with active businesses and traffic lights and people out and about. And just like every small town in Nevada (it seems), Winnemucca has a casino or two. Truth told, from the street they kind of look like a Walgreens or CVS pharmacy with a little extra makeup; otherwise they bear little resemblance to their brethren on the Las Vegas Strip. Like Wyman though, I’m not much of a gambler, so I ride by.

I’ve done about 75 miles this morning so I need a charge. The map says that there’s a Tesla SuperCharger in town but it doesn’t work with the Zero. I stop at Winnemucca RV Park, a mom and pop place smaller than the larger RV parks a little further on. Personally, I’ve got a soft spot for the small, family-owned joints and prefer visiting them; I’ve also made a conscious decision to try to eat all of my meals at local restaurants, not chains. I park and walk into the office/convenience store which has a friendly, down-home camp store vibe with people chatting about the weather and nothing in particular while taking advantage of the air conditioning. It feels good.

They want just $2 for a charge. I park in the far corner, next to the resident handyman who seems to enjoy chatting and helping others with little things that need to be fixed. He gives me a bottle of water as I charge and invites me to use his picnic table in the shade. Another fellow comes over and we get to chatting about my trip. He’s from the Pacific Northwest and is here visiting family. We talk about the electric motorcycle. We talk about Wyman. He says that the fishing isn’t so good around here. We laugh.

The temperature has reached full midday Nevada in July hot. I amble back to the office for an ice cream sandwich and a red Gatorade. The park is pretty basic, just a large patch of light crushed gravel with RV parking spots around the perimeter and two aisles in the center. There’s a tree here and there but that’s about it. The bathroom is spotless though, which is always nice. I’m hungry but I’m told that the only place within walking distance, a Mexican joint, isn’t very good. After getting a charge, I grab a late lunch down the road before hitting the highway.

Meanwhile, back in 1903, Wyman had another fall somewhere between Winnemucca and Battle Mountain. This one was more serious than the previous falls:

"…I came to a place where I ran the motor at top speed for 10 miles. Then my handlebar broke while I was going full-tilt, and I had a close call from striking my head on the rail. I missed it by a few inches. After a walk of a mile I reached a boxcar camp and got a lineman to help me improvise a bar out of a piece of hardwood, which we bound on with tarred twine. I made as good a job of it as possible, for it is a poor country for bicycle supplies, and I realized that I would not be able to get a pair of new bars until I got to Ogden, nearly 400 miles beyond…"

George A Wyman

Remember that motor bicycle you built a couple of pages ago with old stuff from your basement or garage? Now take a hacksaw, cut off half of the handlebar, and then get an old broomstick and cut it to the length of the handlebar that you just cut off; you may want to add another eight inches or so to secure it. Secure the broomstick to the remaining part of the handlebar with rope, twine, cable, long zip ties…whatever. Make it nice and secure. Now ride 400 miles with it like that. No, not on paved roads. On trails and railroad tracks.

It should also be noted that the motorcycle helmet was still 11 years from being invented so Wyman was obviously not wearing one. Crashing while going "full-tilt" (Wyman said the he could go 12 mph on the railway ties) and striking the iron rail with his head would have hurt a fair bit and quite possibly injured Wyman enough to end his trip…or worse. And unlike modern impact absorbing and abrasion resistant motorcycle apparel, Wyman’s coat, waistcoat, leggings, and cap provided little crash protection.

The hard miles in the sand and on the rails were beginning to take their toll on Wyman. By the time he arrived in Battle Mountain he considered giving up.

"…to tell the whole truth, I went to bed thoroughly disgusted with my bargain. I felt as if I was a fool for attempting to cross the continent on a motor bicycle. I was tired of sand and sagebrush and railroad ties. My back ached, and I fell asleep feeling as if I did not care whether I ever reported to the Motorcycle Magazine in New York or not."

George A Wyman

At this point he had made it farther than Alexander Winton had in 1901 in his automobile and had ridden farther eastward than anyone before him, automobile or motorcycle. That is no small feat and nothing to be ashamed of. But he’d only gone about 500 miles and had 2,500 plus challenging miles ahead of him. He was already tired and sore and discouraged. It's no wonder he thought about quitting. Most would have quit sooner.

On the same day that Wyman struggled to make it to Battle Mountain, another cross country attempt was leaving San Francisco. As the story goes, less than a week after he made a bet that he could drive a car across the country, Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson had secured a co-driver/mechanic (Sewall K. Crocker, a bicycle racer/mechanic/driver from Tacoma, WA), purchased an automobile (a used, 20 horsepower Winton), purchased a car load of provisions, and set off for New York City. Their plan was to heed Winton's advice and avoid the desert sands of Nevada altogether, instead heading north into Oregon and Idaho.

Another great installment! I love driving through Nevada, but I can’t imagine doing it without a road. Travelers had to be so much tougher 100 years ago.