[The story begins here… I recommend viewing on a laptop or desktop or even a tablet to let the photos breathe a little more and help convey the vastness of the American West.]

May 23, 1903 — Humboldt, Nevada

"The people in that country did not get up early enough to suit me, and I left Humboldt at 5:40 a.m. without breakfast. I struck sandy going at once, and took to the everlasting crossties and kept on them nearly all the way to Winnemucca, 45 miles from Humboldt. Seven miles west of Winnemucca I came to a stretch where I could see the place in the distance, and I left the railroad to take what I thought to be a shortcut over a trail that runs along an old watercourse, diverging gradually from the railroad."

George A Wyman

July 15, 2016 — Lovelock, Nevada

The morning sun peeks through the blinds of my little hotel room at the Cadillac Inn and makes my eyelids glow red. The air conditioner still sounds like a two pack a day smoker but at least the room is cool. I open my eyes and my crap strewn about as if my saddlebags exploded like a snake-in-a-can gag. "How is all of this stuff mine?" my pre-caffeinated mind wonders. I have the same exact thought nearly every morning. I get up and put on a clean(ish) pair of pants and a fresh shirt. I give my wool socks a quick sniff…hmm, these should be good for one more day (a little white lie I tell myself nearly every morning) before putting them on. I tuck my pant legs into my boots, cinch them securely, and then follow the extension cord out the door to the Zero. It's a cool morning in Lovelock, Nevada with a thin sheet of clouds overhead. The bike is 100% charged so I pull the plug from the bike and gather the extension cord in loops as I walk back to the room. The cord is warm to the touch. Note to self — get a heavier gauge extension cord ASAP. I walk back to the bike and put the cord in the topcase and then head back to the room.

My riding gear hangs by the door, my helmet and gloves are on the small refrigerator, and my saddlebags and backpack are on the floor. My phone, tablet, and camera battery charger dangle from a small power strip by the microwave and television. In the bathroom, a hand washed shirt and pants are drying and my dop kit sits on the bathroom counter. I soak a paper towel in the sink to drape over my helmet visor to soften yesterday’s buggy grime. The stiff-soles of my boots make me sound like a gelding as I walk across the tile floor.

I methodically gather each and every piece of gear and put it back where it belongs. The camera gear and water bottle go in the backpack, the dirty clothes go in one packing cube in one of the saddlebags, the (ostensibly) clean clothes in another packing cube in the other saddle bag. The running shoes get wrapped up in a plastic bag before being put in their place. The power strip and various charging cables are carefully wound and put in their own bag before being put in a saddlebag. I bend over and pick up the saddlebags to feel their weight; they need to be balanced. A place for everything and everything in its place. It’s a hard-learned lesson. If I didn’t, I’d be sure to forget something. I look at the now-tidy room and remember what it was like just 15 minutes ago and wonder, "How’d it all fit into these bags?" I do this every morning.

I pull my riding pants on over my synthetic street pants and zip the outer zippers down from my hips to my ankles. The Cordura makes a sandpapery scratchety sound with each step. I give the room a once-over to make sure I’m not leaving anything behind. One more stop in the bathroom to clean the helmet visor and collect the room towels.

The tops of the saddlebags are rolled over and over and then cinched shut. I carry them out to the bike and drape them over the passenger seat, securing them to their tiedown points on the passenger footpegs. I step behind the bike to see if they are level, but the bike is leaning onto its sidestand so it’s hard to eyeball. Sometimes I get it very wrong and on the road must look like a drunk with a leg length discrepancy; I try to look cool on the bike but the inner dork wins more than I'd like him to.

I go back to the room one final time and leave a tip on the dresser, place the keys on top of the tip, and walk out. I place the phone in its handlebar cradle, plug it into the bike’s 12v outlet, put in my earplug headphones, put on my jacket, and pull on my helmet. I swing my leg over the saddle and straddle the bike. I start the motorcycle. Apart from the dashboard going through a choreograph of lights and flashes, the Zero is silent. I launch the phone map and punch in my next destination. I start some music, put on my gloves, twist the throttle, and quietly whirr away from Lovelock, Nevada.

[ALT: Time lapse video of white, puffy clouds rolling the flat, dry desert of Nevada. Distant mountains are on the horizon and eastbound and westbound lanes of the interstate run from the bottom of the frame to the distant horizon]

Cloud cover keeps a lid on the heat and the riding is mellow and relaxed as I explore empty local roads that run parallel to I-80. Sandy soil and patchy sagebrush extend for miles in every direction. Angular, barren, rugged mountains ring the distant, hazy horizon. The interstate runs arrow straight across the plain, two black stripes in the Nevada desert.

Besides the small towns linked together by I-80 and the railroad, there’s not much evidence of human existence in this part of Nevada. There never has been. The state had just 42,000 people in 1900, which is 0.37 people per square mile. If you round that down like they taught you in elementary school, that’s 0.00 people per square mile or, in the more common vernacular, nobody. Even today there are only 26.8 people per square mile in the state, or about half a Greyhound bus. Take Las Vegas and Reno out of the equation and the number plummets to 5.13 people per square mile, or one midsize sedan. In other words, still basically nobody.

The map on the phone shows a waypoint for Humboldt, where Wyman stayed for a night. He wrote, wryly,

"Humboldt is a pretty place. You are convinced of that when you look at the surrounding country, which is desert waste. All there is of Humboldt is shown in the picture of it that I snapped with my little Kodak. The house that occupies the foreground, background and sides, and which surrounds the town, is that of the station agent, telegraph operator, and keeper of the restaurant for the passengers."

George A Wyman

The handful of buildings that comprised Humboldt in 1903 are no longer there. There’s an exit for Humboldt on I-80 that leads to little more than a handful of houses on one side of the interstate and a mine on the other.

When the Transcontinental Railroad was constructed, workers also constructed new telegraph lines to replace the original transcontinental telegraph line from 1861. That line, completed during the Civil War, revolutionized communications, shortening coast to coast communications from ten days (via the Pony Express) to minutes. The first message transmitted was to express California’s support of the Union in the war.

In the temporary absence of the Governor of the State I am requested to send you the first message which will be transmitted over the wires of the telegraph Line which Connect the Pacific with the Atlantic States the People of California desire to Congratulate you upon the Completion of the great work.

They believe that it will be the means of strengthening the attachment which bind both the East & West to the Union & they desire in this the first message across the continent to express their loyalty to that Union & their determination to stand by the Government in this its day of trial They regard that Government with affection & will adhere to it under all fortunes

Stephen J Field

Chief Justice of California

Two days after completion of the line, the famed Pony Express, just 18 months in business, shut down.

Early mapmakers imagined a great river draining the Rocky Mountains and running westward through Nevada, something akin to the mighty Mississippi River and upon whose broad waters pioneers and merchants could float all the way to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. They were so confident that they named this mythical river the Buenaventura or "Good Luck" River even before finding it, but early pioneers quickly discovered that the mapmakers were wrong. What they found instead was the Humboldt River, originating at a spring near Wells, Nevada. It was not very well liked by the pioneers.

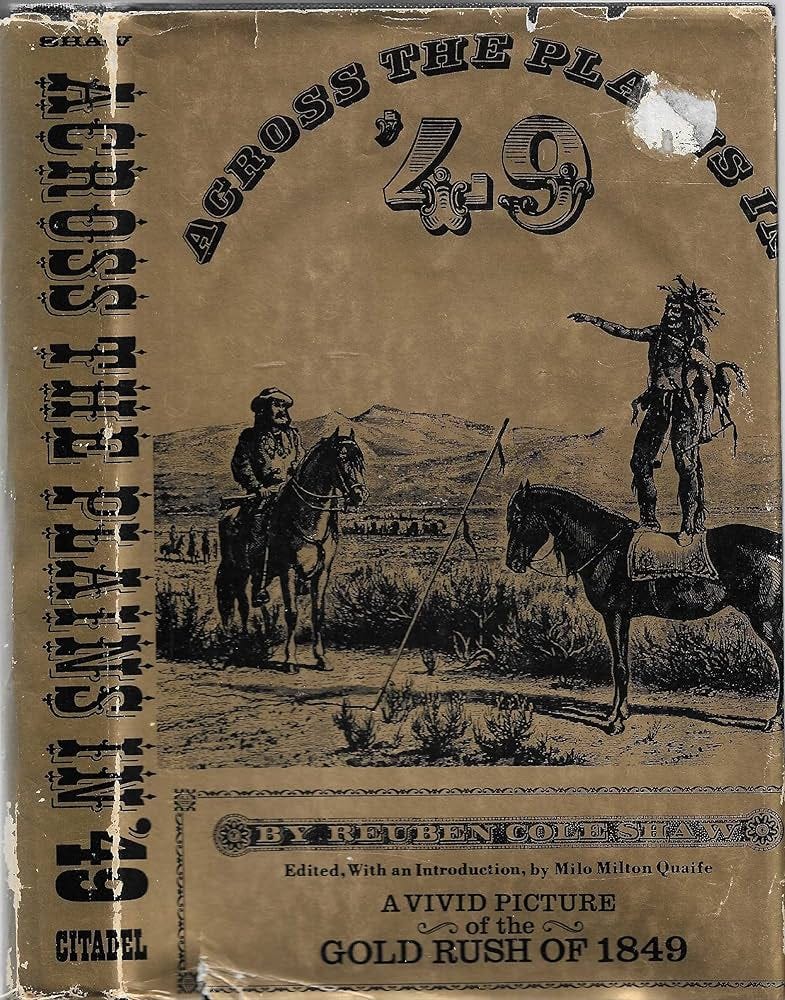

"[The] Humboldt is not good for man nor beast...and there is not timber enough in three hundred miles of its desolate valley to make a snuff-box, or sufficient vegetation along its banks to shade a rabbit, while its waters contain the alkali to make soap for a nation."

Reuben Cole Shaw, 1849

"Meanest and muddiest, filthiest

Stream, most cordially I hate you"

Dr. Horace Belknap, 1850

The unloved Humboldt River does not make it to San Francisco as they thought the mythical Buenaventura would. In fact, the Humboldt doesn't even make it out of Nevada, disappearing in the aptly named Humboldt Sink. On Google Maps, the Sink is colored green and looks like a lush, reservoir but look at the satellite map and you'll see that it's really a giant dry nothingburger of sand, the place where the Humboldt River goes to die. Despite the hatred for the Humboldt River, it was a key feature of the California Trail and helped emigrants cross a harsh landscape.

[ALT: Video of capture of Google Map of the Humboldt Sink. When viewed as a map, there are vast areas of blue, suggesting a lake or other body of water. When viewed as a satellite photo, it is mostly arid desert, with the Humboldt River entering the frame from the right (East) and emptying into small maze of wetlands.]

Excellent and interesting installment!