[The story begins here… I recommend viewing on a laptop or desktop or even a tablet to let the photos breathe a little more and help convey the vastness of the American West.

July 16, 2016 — East of Wells, Nevada

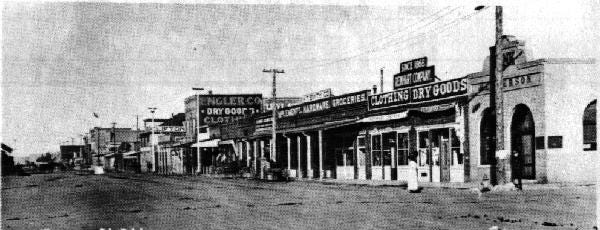

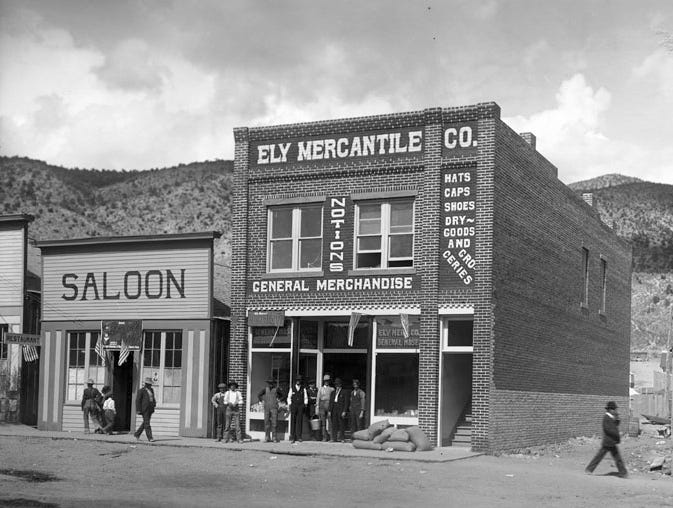

"The divisions are places where the freight and passenger trains change engines. Quite often they are something of places, with from 200 to 5,000 population. There, two or three hotels will be found, several saloons, and a couple of stores. The stranger marvels to find a community even of this size in such a God-forsaken country. He wonders why anyone lives there, but if he is wise he does not ask any such question, for even though the wildest days have passed, it is a hot-blooded country still, where fingers are heavy and guns have hair triggers. At the division settlements in the heart of these wildernesses there is a great deal of home pride, and the traveler can get along best by praising the place he is in and 'knocking' the nearest neighboring settlement.

George A. Wyman

These settlements are supported partly by the money that is circulated by the railroad employees, the passengers who stop for meals and the ranchmen who come into the valley of the desert 'to town' to get mail, ship goods and have a good time. These division towns are the rendezvous of the polyglot laborers on the railroad sections and the sportive cowboy alike, and as these elements don't mix any more than oil and water, there are some 'hot times in the old town' occasionally. The reason why there is no more trouble than there is 'shooting up the town' is that wily sheriffs 'round up' the ranchmen when they strike town. Then it's a case of 'Now, boys, let me have your guns we don't want any trouble, and I'll take care of your shooters - let’s be reasonable.' The boys are reasonable and as the sheriff treats all alike, they hand over their shooting irons and they are tagged by the sheriff with the owner's name and kept by him till the spree is over. Occasionally, though, the men get to drinking and the fun begins before the sheriff is aware there is a party in town."

George A. Wyman

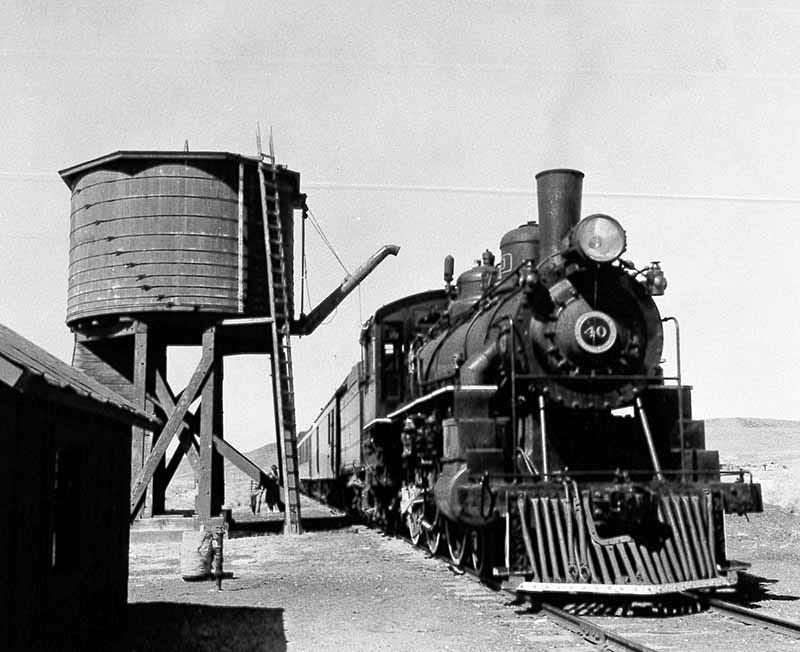

While the U.S. Census had already declared the western frontier closed in 1890, thanks to pioneers and homesteaders settling the west, it’s clear that the frontier spirit still lived in Wyman’s 1903. But between the Civil War and the First World War, the railroad reshaped America, connecting the country in a way that had never been seen before. The futures of cities and towns were directly tied to the railroad. Wherever the railroad stopped, a town grew, and nearly every major city in the West exists because of the railroad.

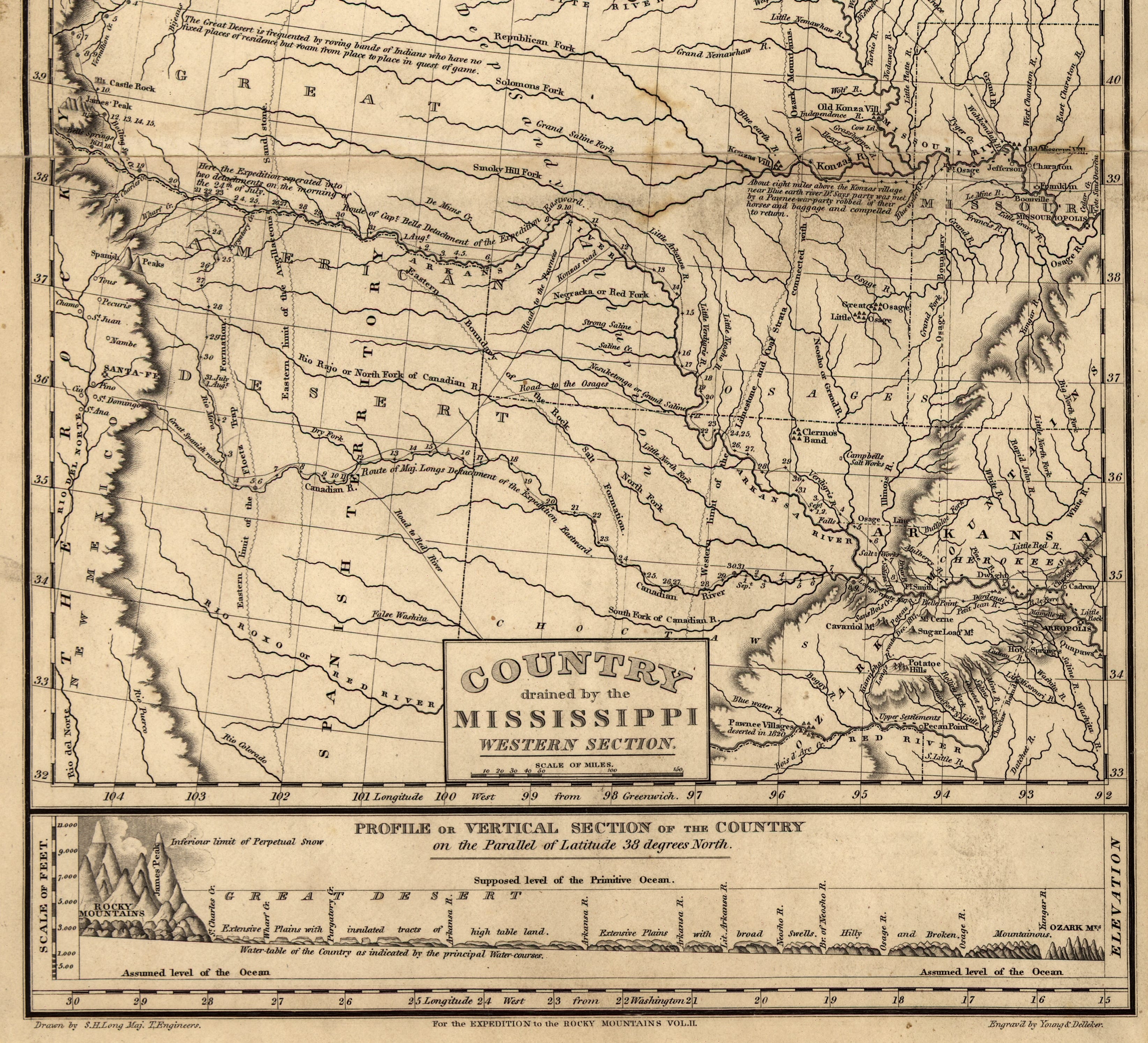

"The Great American Desert, which stretches from Elko, Nevada, to Kelton, Utah, is nearly 200 miles across, or 5 times as big as the first one. I struck the alkali sand of the Great American Desert going out of Wells, and for three miles found a stretch hard enough to ride on. Then I walked for two miles, and went over the railroad, where I found fair tie-pounding. I was interested in this part of the desert to find that the picturesque old prairie schooner of the Forty-niners, who traveled this overland trail, is not extinct. I passed quite a few of them at different times. Most of them carried parties of farmer families who were moving from one section of the country to another, and several were occupied by gypsies, or rovers, as the natives call the Romany people."

George A Wyman

What Wyman calls “The Great American Desert” is now more commonly known as the Great Basin Desert. In the 1800s, some called the area between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains “The Great American Desert”. These days, this area is known as the High Plains.

Another benefit of traveling along the Transcontinental Railroad was water. When the railroad was constructed, they built water towers for the steam locomotives and telegraph towers every twenty miles or so. Steam locomotives were still in widespread use in 1903, so Wyman had regular access to water across the Nevada desert.

"This day, between Wells and Terrace, May 26, 1 had two experiences more interesting to read about than to pass through. It is rather high altitude there, the elevation at Wells being 5,628 feet, and at Fenelon, the name of a side switch without a house near it, 20 miles east, the elevation is 6,154 feet. There was a heavy frost on the ground in the morning when I left Wells at 6 o'clock, as, indeed, there was nearly every morning during that week. It was bitter cold, and before I had gone 20 miles my ears were severely frosted. There was no snow to rub on them though, and I had to doctor them the best I could with water first and then lubricating oil. In the afternoon of the same day it grew very hot, and my ears got badly sunburned, in common with my face. That gives an idea of the climate of the country."

George A Wyman

The high desert is a place of extremes. During the summer days, the heat falls from the sky and radiates from the pavement, shade is as rare as hen's teeth, and a light breeze feels like a hair dryer. It's a dry heat, they say, which is supposed to make you feel better about the thermostat reaching into the high nineties but all it really does is chap your lips and dry your face and hands. But winters can be freezing cold, and during the Spring (when Wyman was traveling) hot days are chased away by cool nights. By July, when I was crossing the high deserts, the heat is persistent, crawling out from the heat-soaked earth long after the sun has fallen off the horizon.

The riding gear that I wear is modern and high tech (I have a backpack with solar panels, for crying out loud!) and will help protect my skin and bones should something go wrong and I find myself suddenly and unexpectedly separated from the motorcycle. The jacket is even made for riding in the summer heat, with vents and perforations that are designed to let air flow through and keep me cool. But here in the dry Nevada heat, that’s kind of like expecting the car fan turned to high but the A/C turned off to do much cooling at all.

"The railroad built a couple of buildings to house section crews. Pequop is located high in the mountains, and snowplows were constantly needed to keep the tracks clear of snow…During the 1930s, enough people lived in Pequop to warrant the opening of a school for five students...The coming of diesel locomotives to the railroad in the 1940s reduced Pequop's usefulness. By the end of the 1940's, only a couple of railroad workers were left. All of the buildings are gone, and only foundations and scattered debris are left."

Shawn Hall, Connecting the West

The road beelines eastward across the broad Independence Valley towards a jagged horizon line known as the Pequop Mountains. A 51 mile long barrier between Independence Valley and Goshute Valley, the Pequop Mountains rise as high as 9,200 feet and were a formidable barrier to the pioneers and the Transcontinental Railroad. They grow with each mile until they fill my visor and the roads rises to meet them. Unlike the pioneers, the railroad, and Wyman, who skirted north of the mountains, I-80 simply barrels over them in a series of long, steep grades.

I look up towards Pequop Summit and see something that I haven’t seen since the Sierra Nevada - green. Not just a lone tree or a stand of vegetation along a riverbank, this is a blanket of green thrown over the mountain. It’s threadbare in spots but it’s the most green that I’ve seen in the whole state of Nevada. There's just one small problem — it’s on fire. The road bends into Maverick Canyon and a plume of white smoke rises from somewhere near the peak. As the road climbs the plume grows and changes color from pure white to a brownish grey. I get closer and have to crane my neck to see it, a humongous tower of smoke. At the top of the pass (6,967' and the highest point between Donner Pass and the Wasatch Mountains in Utah) it’s clear that it’s a forest fire. Straight off a movie set, a man on a horse is riding quickly to the source of the fire. High altitude winds blow the smoke northward. Thankfully, the fire is not too close to the road, and I'm relieved to be descending the mountain and leaving the conflagration in my mirrors.

I turn off I-80 and head north, the fire now on my left. The smoke is now rising thousands of feet into the sky, making the mountains and the land feel small in comparison. I stop to take a photo. It’s just me out here. Minutes pass before I see a car.

"MONTELLO

POP. 193

ELEV. 4880"

That's what the faded, rough hewn wooden sign says at the edge of this dusty little town in the middle of nowhere. On the left is a motel and gas station (the only one for fifty miles), a couple of small bars, and a fistful of houses scattered on a sandy grid of unpaved streets. On the right is the railroad and, across a broad plain, a string of sharp 7,000 foot mountains. That's Utah and I can see it from the gas station.

Smoke from the Pequop forest fire floats across the late afternoon sky. I really wanted to reach Utah today but it's already late in the afternoon and there's a long stretch to the next charging opportunity. It would be stressful watching the clock and watching my battery level but I could probably do it. I look once again across the street and across the railroad and across the barren plain to those sharp 7,000 foot mountains in Utah turning a shade of gold in the late afternoon sun. I could spend the evening just staring at those mountains, I think. So that's what I decide to do. I ask about a room and a place to charge; they have both. The place is run by a couple from California that were deep into the Orange County lifestyle and then one day were just fed up with the traffic and the stresses of modern life and checked out, so to speak, and relocated to Montello. Pop. 193. I unpack, grab dinner at the Cowboy Cafe, then sit and watch the mountains.

I'm on the edge of the 21st century here; it’s towns like this that make you realize that humanity's grip on this planet is tenuous at best, and should we manage to annihilate ourselves, the searing sun and winds of time will quickly erase nearly all evidence of us.

Many people have told me how boring crossing Nevada was for them. My experience was totally different. When you spend all day on a motorcycle beneath the dry withering heat without the benefit of air conditioning you really begin to appreciate the size and severity of this place. For a boy from New Jersey, it feels alien, and the land is so big and the sky so huge here I can almost see the curvature of the Earth. I imagine George A Wyman out here all alone, nothing but him, the land, the sky, and the railroad. And then I imagine those that came through here before Wyman, like those Union Pacific Railroad workers in the 1860s aiming a pair of iron rails across a vast emptiness for a meeting with manifest destiny in Promontory Utah. And before them even, to those that rode stage coaches across these vast stretches, and those before them that placed all of their worldly possessions in a covered wagon and ventured across these plains in search of a better life, and even before them to the Paiute and Shoshone who traveled this land. My journey, in comparison, is a walk in the park.